On December 6th, 1991, the original crew of the U.S.S. Enterprise – Kirk, Spock, et al – took their final voyage aboard the iconic starship with “Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country,” the swan song of the original cast movies (since then, we’ve had four “Next Generation” pictures as well as three of the J.J. Abrams-produced reboots). While the series already had a rich musical legacy with music by luminaries such as Jerry Goldsmith and James Horner, “Star Trek VI” would boldly go with a relatively young and inexperienced composer.

Cliff Eidelman was a student at the University of Southern California when he submitted a demo to Paramount, who had put the call out for younger composers simply because of budgetary constraints. Director Nicholas Meyer, who cemented his place in the franchise’s history with 1982’s “The Wrath of Khan” (still seen today as the best of the thirteen movies), hired Eidelman but initially wasn’t interested in an original score. Instead, he wanted the composer to arrange the famous suite “The Planets” by the British composer Gustav Holst, a curious idea but one albeit not completely original.

Rumors have constantly swirled in regards to “Star Wars,” and George Lucas apparently wanting to licence Holst’s suite and other classical works for his space epic after the success of “2001: A Space Odyssey.” Lucas was eventually convinced to go with an original score from John Williams, who used influences from Holst to Korngold to Herrmann to create a neo-classical symphonic tapestry. Lucas had also created a temp-track of the likes of Stravinsky and Rozsa, and used a snippet from Vivaldi’s “The Four Seasons” to score the first trailer for his film. But with the sheer cost of licencing such music, Eidelman’s demo compositions won him the chance to create his own score - a mysterious, tense, and beautiful work encapturing the romance and danger of space travel in similar ways to Goldsmith and Horner.

The score for “Star Trek VI” is different from the opening frame, with a slow-burning piece steadily building over the opening credits, dominated by a six-note ascending/descending phrase that would become the “conspiracy” theme for the picture. Intentionally designed by Meyer to be something other than the usual big march that tended to open the previous credit sequences, the sombre and questing tone helps the main title become a part of the narrative, with the taut score building and building to that memorable post-credit moment where the Klingon moon Praxis explodes.

That’s not to say the movie doesn’t feature a more traditional main theme; Eidelman’s bright and sweeping piece for the “undiscovered country” the Enterprise and her crew are headed for is wonderfully majestic. The cue ‘Clear All Moorings’ gives the theme its maiden voyage as the starship leaves spacedock in a grand nautical “Star Trek” tradition, but it also works in an introspective and reflective mode, which is important given the film’s status as the last one featuring the original crew. It also fits beautifully with the Alexander Courage television series fanfare, which is used sparingly until it’s appropriately brought back to close the picture.

Eidelman also uses interesting colours and textures for the more alien material. A highlight is an ethereal and glasslike theme for Spock and his successor Valeris that has a certain fragility, perhaps foretelling the way the relationship plays out in the story. Flashes of brutal and bellicose brass score the icy prison planet of Rura Penthe where Kirk and McCoy are sent, along with a male choir that recalls some of Jerry Goldsmith’s terrifying choral work on “The Omen,” with the subsequent prison escape and the spectacular snowy vistas letting Eidelman break loose with some big evocative string moments reminiscent of Maurice Jarre’s scores for the films of David Lean.

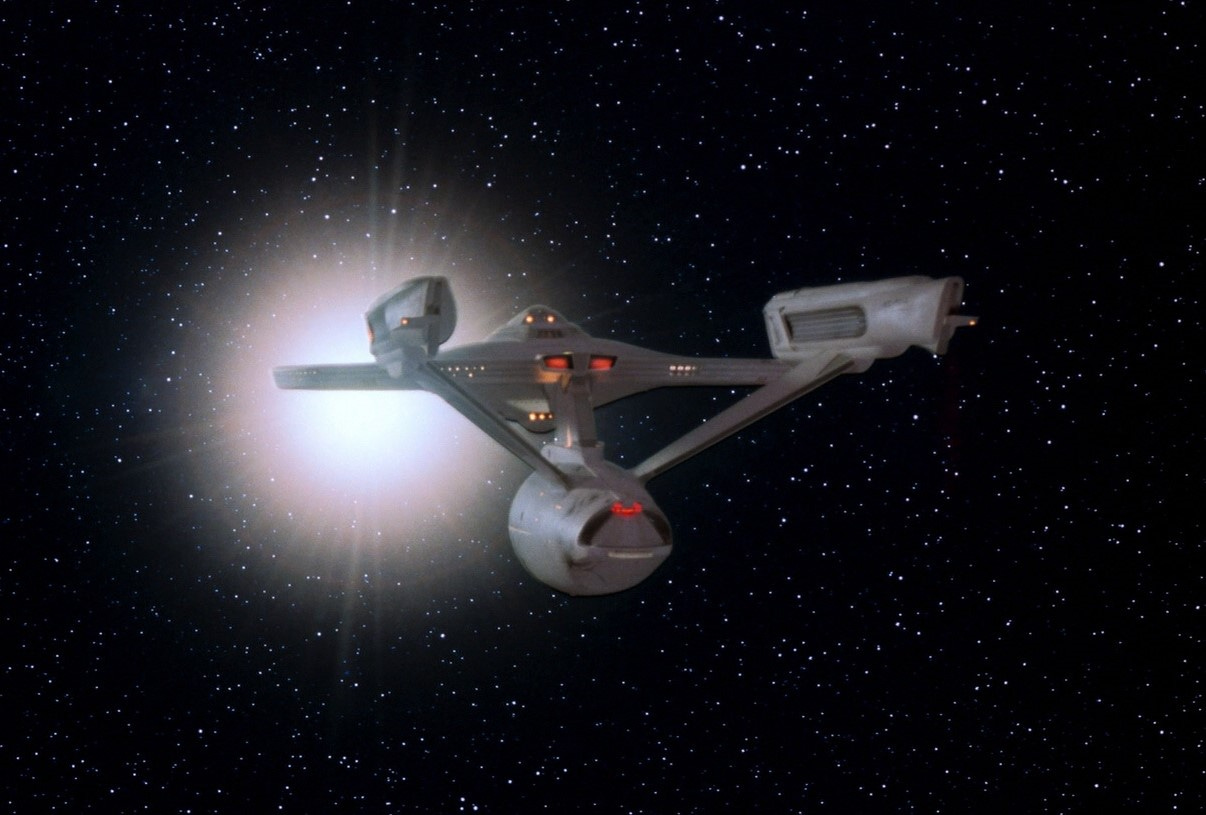

The final big action sequence as the Enterprise takes on the Klingon warship is not only brilliantly tense but also thematically consistent, revisiting the opening title material but opening it up majestically with the conspiracy theme driving everything. Eidelman then uses the undiscovered country theme to wrap everything up in a gallant and noble tone, celebrating the first seeds of peace between the Federation and the Klingons before the crew is given a suitably wonderful final sign off. With Spock answering a request for the Enterprise to be decommissioned by uttering the now iconic “If I were human, I believe my response would be… go to hell,” the Courage fanfare signals the beginning of a new journey into the unknown – to say goodbye to the gallant crew and the spaceship that has been a part of our hopes and dreams since the late sixties.

As William Shatner’s Kirk gives a final log entry that signals the hand-off to the next generation who will be “…boldly going where no man, or no one, has gone before,” the Enterprise disappears into a star as the famous fanfare swells exponentially - the farewell to the final frontier. In a lovely touch, the signatures of the cast are presented upon the screen, again capped off by that iconic fanfare that has meant to much to so many. The essence of “Star Trek”; a call to arms for humanity.

Over thirty years later, “Star Trek” has experienced many more highs and lows, with music from many different composers, and is once again a mainstay on television. Cliff Eidelman’s score underlines the core tenets of the franchise just as “Star Trek VI” as a film does, not just a space opera but an exploration of the complexity and fragility of the human body and mind, emotions, prejudices, and that which has nurtured and influenced those. To respect what has come before, but not at the expense of what it means to be human, and to celebrate those marvellous infinite diversities in infinite combinations.

Fascinating.