When is a werewolf movie not a werewolf movie? When it's “Wolfen.” 1981 was a special year for the cinema of the lycanthrope, with three spectacular offerings in the guise of Joe Dante's “The Howling,” John Landis' “An American Werewolf in London,” and Michael Wadleigh's “Wolfen.” But while the Dante and Landis films are very traditional monster pictures rooted in the mythic landscape of the American horror movie, Wadleigh wanted a more unique angle and looked towards the world of politics as well as parts of American history that would pre-date the cinema by thousands of years.

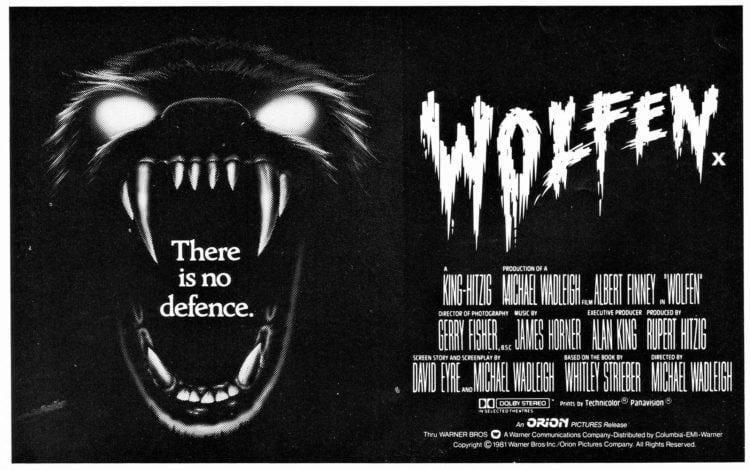

To say “Wolfen” has had a tempestuous journey throughout its lifetime would be a major understatement; from its post-production power struggles to a box office release far below its budget and expectations to its slow rise to being considered a respected genre film, if not afforded the "classic" label given easily to so many of its ilk that were reappraised in the home video age. It still lives in the shadow of “The Howling” and “An American Werewolf in London” and probably still will for the remainder of its life, but anyone who has seen it will tell you its antagonists hunt from the shadows. And as the one-sheet tagline stated, "They can tear the scream from your throat."

The tale of “Wolfen” began on the printed page. In August 1978, book publisher William Morrow & Co published “The Wolfen” by Whitley Strieber - his debut novel. Similar to the then-recent “The Howling” by Gary Brandner, which was published in 1977, the rights to Strieber's novel were soon optioned by fledgling studio-elect Orion Pictures. While the themes of the book and the film would eventually diverge quite significantly, the basic bones of the story are the same: two New York City detectives named George Wilson and Rebecca Neff are tasked with investigating several homicides across the city that are bringing up disturbing questions involving canine attacks. After collaborating with medical examiner Evans and animal expert Ferguson, it's decided that what Wilson and Neff are facing aren't just dogs or even wolves, but werewolves.

The werewolves as described by Strieber aren't the traditional monsters we've come to associate with the name; there's no shape shifting, no full moons. Instead a separately evolved creature with frightening intelligence. Strieber uses mythology and literature to support the theory of not only the werewolf but also how it disappeared, away from man. In a passage from the novel, Ferguson reads an old tome about werewolves and posits on their journey through history:

"Here were legends, stories, tales going back thousands of years, repeating again and again the mythology of the werewolf. And then suddenly, in the latter part of the nineteenth century, silence.

The legends died.

The stories were no longer told.

But why? To Ferguson's mind the answer was simple: the werewolves, tormented for generations by humanity's vigilance and fear, had found a way to hide from man. Their cover was now perfect. They lived among us, fed off our living flesh, but were unknown to all except those who didn't live to tell the tale. They were a race of living ghosts, unseen but very much a part of the world. They understood human society well enough to take only the abandoned, the weak, the isolated. And toward the end of the nineteenth century, the human population all over the world had started to explode, poverty and filth had spread. Huge masses of people were ignored and abandoned by the societies in which they lived. And they were fodder for these werewolves, who range through the shadows devouring the beggars, the wanderers, those without name or home."

Survival is the ultimate goal of the Wolfen and it's something that is very much put into jeopardy by Wilson and Neff's investigation, being that the humans have discovered the Wolfen's existence after first finding two men dead in an emergency services car yard. The pack are concerned, and here Strieber injects a sense of hierarchy with the elder werewolves being in charge as you might imagine, but the younger animals needing to prove themselves. This leads to somewhat of a schism when the pack discovers it was two of the younglings that not only killed the men in the car yard but also clumsily did not retrieve their bodies.

It was clear that Strieber's novel would make a good candidate for a screen adaptation, and would eventually catch the eye of a perhaps unorthodox choice for director: Michael Wadleigh. Wadleigh had made his name in documentaries, and one in particular, 1970's “Woodstock,” and while this may not have put him as the obvious person to direct a movie about werewolves tearing people's throats out, the ecological and sociological aspects attracted him. "I spent a lot of time after Woodstock writing about a dozen screenplays with my girlfriend of ten years, Dulcida Gose," Wadleigh told Fangoria in 1981. "They received a lot of attention, but were basically too expensive and too political to produce. Mike Medavoy, vice-president of Orion, particularly liked those scripts and sent me several properties that they had acquired to see if I'd be interested in adapting and directing them. Now, my interest in films has always been social and political, not entertainment. But what I've realised over the years is that no one watches PBS. Documentaries are often preaching to people who are liberal already, so what's the point? What interested me about ‘Wolfen’ was the opportunity to use the horror genre as a departure point. I like the fact that while we could entertain audiences and satisfy their ghoulish fantasies, we could also get some interestin points across that might enrich their lives."

However, Wadleigh and co-screenwriter David Eyre felt they needed to transform parts of Strieber's novel for its journey to the big screen. Wilson, as played by Albert Finney, was given a new first name of Dewey, and his partner Neff (Diane Venora) was a visiting criminologist instead of his regular partner. The misogyny of Wilson's character in the book was removed, as was Neff's husband taking bribes to pay for his father's expensive care home. Evans became Whittington (Gregory Hines), a young and hip medical examiner, while Ferguson remained as played by Tom Noonan. The initial victims however changed drastically; instead of the two guys in the yard, the first killed was construction magnate Christopher Van der Veer, his wife, and their security guard. These victims then linked into the larger screen story as Wadleigh and Eyre underlined the Wolfen's connection to America's indigenous tribes of Native Americans, something made much more explicitly in the film.

"What appealed to me about ‘Wolfen’," Wadleigh said, "was its underlying allegory about nature. I wanted to play that up much more in the film. The genesis of the Wolfen's culture is that when white man first came to America, he came as a farmer. His two basic enemies were the hunting tribes: wolves and Indians. White farming man wiped them out, the forest, and the great American buffalo out. We reduced the wolf population from a high point of two million to fewer than one thousand. What's fictional in our screenplay is that the Wolfen are the product of biological/artificial selection. When we destroyed the original wolf population, only the smartest survived. Their forests were all gone, so they moved into the new wilderness: the slum areas of the major cities. For survival, they hunt at night. For protection, they only eat people that our society doesn't give a shit about, the inhabitants of the slums. These people are never missed so their murders are never looked for. Being humanitarians or 'wolfitarians', as they are also are in Whitley's book, the Wolfen only take people who are essentially ready to die. It's almost an eastern philosophy of euthanasia."

The Native Americans in the film are primarily represented by Eddie Holt, played by Edward James Olmos in one of his early roles. Olmos gives a mesmerising performance in the film, and it cements the spiritual connection between the Native Americans and the Wolfen to the point where it allows for a certain degree of ambiguity as to what they actually are. Speaking to Fangoria in 2011, Wadleigh stated "An amazing thing that I believe is mentioned in the film is that the Dutch colonists who first settled in New York actually used the same word — wolfen — to describe both the Indians and wolves. They of course knew the difference, but there were quite a few wolves around at that time, and those early colonists denigrated the Indians as savages and really felt they were different from full human beings. They felt that the wolves were so scary and powerful —and this fear came out of European mythology as well— that they actually elevated the wolves’ intelligence and lessened the Indians, and in doing so sort of drove them together so that they were pack animals that were wild and ferocious. That was the central interesting issue for me, that the Dutch were pushing the Indians and wolves together. Therefore you kind of had a bifurcated personality, and they were after all shapeshifters. Well, we put it in the film when Eddie Holt shapeshifts on the beach. You have them sometimes looking like Indians and sometimes like wolves."

"The whole backdrop is what we did to the Indians, and the reason I killed off Van der Veer is also made clear: that his great-great-ancestor reputedly brought the first machine to America— the windmill —and that machine stands for the Industrial Age and the supposedly superior technology of the Europeans that just wiped out the Indians." There is also a crucial scene where Holt explains the nature of the Wolfen to Wilson, who finds himself in a Native American bar after Whittington is killed. "It's not wolves," Eddie states with fire in his eyes, "it's Wolfen. For 20,000 years Wilson -ten times your fucking Christian era- the 'skins and wolves, the great hunting nations, lived together, nature in balance. Then the slaughter came. The smartest ones, they went underground. Into the new wilderness, your cities. Into the great slum areas, the graveyard of your fucking species." Wadleigh said he took great care to not make the scene and the Native Americans like many of those seen in films previously, stating "I've never been satisfied by the way Indians are sometimes portrayed in films, but they seem very real in that scene - very dignified and eloquent and funny. Eddie had hung out with the Indians for quite a while and tried to get the cadence of how they spoke in that kind of clipped way of using very few words."

Eddie also says something else to Wilson that embeds itself: "You got your technology but you lost. You lost your senses." The balance between humanity and technology is at the very heart of the film, and Wadleigh positioned it as a political thriller, where the Wolfen are also hunting for territory, and with the politics and private security companies comes all sorts of special surveillance technology that should make them absolutely safe. But it doesn't. Wadleigh talks of his concept of Wilson "against ancient beasts in the urban jungle. He can no longer uphold the values of a society that he feels is unjust, and now begins to question his own role as a defender of those values and a protector of people like Van der Veer. That’s what I pitched as kind of a way through the piece. Of course, there are no Indians at all in Whitley’s novel, and no political agenda, so you can see that the things I added were very strongly along the lines of a political thriller. I thought I was making a political thriller about a detective investigating activists who are killing off very rich people, and have a political and social agenda that is still made very clear in the movie. The way I photographed and presented the wolves, they never, ever growled or snarled, because that would demean their intelligence and make them stupid in my view. I wanted to make them this shadowy presence that was very much in control of the situation, and even more more frightening. I mean, I was all for killing everyone in sight!"

There's a key parallel in the film with the technology the private security companies use - infrared, variations in heat - and the heightened senses the Wolfen have. The "Alien Vision" as it was called was an early precursor to movies like “Predator” (1987) and used it as a point-of-view for the Wolfen to show just how attuned they are to nature and how they see. Responsible for the effect were cinematographer Gerry Fisher, Steadicam inventor and operator Garrett Brown, and effects expert Robert Blalack, who had previously won an Academy Award for his work on “Star Wars” in 1977. "We wanted to demonstrate wolves' incredible senses;" Wadleigh said, "compared to a wolf, man is blind, deaf and can't smell a thing, so we show you the Wolfen's point of view. We had to come up with a way of filming the fact that wolves can see in the ultraviolet and infrared planes. What we did was to match a scene that we had shot at night during the daytime and lay down a full colour record. Rob Blalack then created mattes by dropping out the day sky and adding a star field. It's not as simple as it sounds, however. The Wolfen see colours that are not quite normal. To show their sense of smell, we used ghosted images. For example, when clues lead Wilson to the South Bronx, the Wolfen see him and make the connection that he's on their trail. After he's gone, they go to the spot where he parked his car. We see a series of ghosted images of things that have been there in the past: people, automobiles... That's indicative of the smells that have been left behind. After all, smells are just molecules."

"We went through a very extensive battery of tests," said Blalack to American Cinematographer in 1981, "searching for the 'day' look and the 'night' look. The night look tests ranged from a black sky to a sky that has graduation in it from blue to green. We did a series of tests where we printed the foreground with natural colour, and tinted the sky a series of colours. We went through just about every possible printing combination that we could come up with and showed Michael Wadleigh and Orion. They arrived at a decision for the night look, and wanted to do more exploration on the day look, so we spent another six weeks experimenting with how the Wolfen see during the day. We had discussions during the test phase as to whether the Wolfen point-of-view should attempt to simulate realistically how a wolf sees. We ran very quickly into a brick wall in that area, as we could not find anyone who could say he had seen through the eyes of Wolfen or wolves. The area is very speculative, and limited largely to dog research. Some researchers feel that dogs see in a monochrome, like black and white, and that they don't experience colour. We rejected doing the Wolfen point-of-view in black and white because it simply wasn't a visually interesting point-of-view. We finally ended up taking the position that what we had to do was to create the idea of how these creatures see, and not the reality of how they see. We hoped to leave the audience with an impression of how another creature might see the world, as opposed to a scientific description.”

What was interesting about “Wolfen” versus similar films of the time was that the film used mostly real animals. There were mechanical wolves created for certain effects, but the majority featured actual wolves. Unsurprisingly, the cast and crew were reticent about filming with animals that were supposed to be wild and fearsome beasts. “"Not only did we have to fence in the area where we were shooting our wolf scenes,” Wadleigh said in 1981, “but Manhattan sent down police sharp shooters. They were under orders to shoot to kill if the wolves got out of the fenced-in area. The other side-effect of using the wolves was that, naturally the cast and crew were afraid of them. The mythology that the wolf is the devil is absolutely permeated through everyone's conscious and sub-conscious. We make use of that in the film by having a church in the Dresden part of the South Bronx. By association, the audience will automatically think that the devil is somehow involved with the murders. The other thing that's scary about the wolves is that they're large. We were working with a 150 pound animal that when it stands up has its head six feet and six inches above the ground. What assuaged everyone's fear was that the wolves are beautiful creatures. Their elegance is disarming. We used that element in the film as well. I think that throughout Wolfen, people will expect that the murder is going to be a hideous werewolf or Alien-type creature. What they finally see are these gorgeous noble animals. The audience will wind up with empathy for them."

With principal photography finishing, Wadleigh looked for someone to create an other-worldly musical soundscape for the film, and his choice was Craig Safan, an up and coming composer who had recently scored Vernon Zimmerman's cult horror “Fade to Black (1980). Unfortunately, while Safan delivered a haunting atonal score, the cracks between Wadleigh and producer Hitzig and Orion were beginning to show. “What he [Wadleigh] really wanted,” Safan told me in 2014, “and what I pitched and what we talked about, was an extremely sound-orientated orchestra using no synths but just have the orchestra play sounds, and we were very influenced by John Corigliano who did “Altered States,” and that kind of composition where the orchestra’s playing more sound events than melodies. And that’s what I was signed on to do, but the problem was that when I got signed and everybody was happy, the producer came to me and said 'I’m so glad you’re doing this Craig cause we really want a kind of John Williams approach' and so I realised that those two people – the producer and the director – really had totally different visions of the film and were not talking to each other. It was a death spiral from there.”

Following that, it is disputed on whether Wadleigh was fired or not, but by November 1980 he was no longer working on “Wolfen.” At the time, Wadleigh told The New York Times “They removed me because I wouldn't cut the film their way. They felt it would be more commercial their way.” Orion executive Bill Bernstein had a different view, stating “Michael was not fired. 'He had his cut of the movie. The arbitrator agreed that Michael's rights under the guild contract were not violated. We had an agreement with the producers, King-Hitzig, for them to have the final cut. Michael was directing his first feature film, and you don't give a first-time director final cut.'' The film remained in post-production under the supervision of director John Hancock, who himself had gone through a similar experience when he was removed from his position as director of “Jaws 2” (1978), to be replaced by Jeannot Szwarc. Hancock and Orion undertook some new filming of the wolves, this time of them snarling and growling. These shots would then be inserted throughout he film, along with growling noises under the “Alien Vision” sequences, giving the film a more traditionally horrific edge but perhaps undercutting the otherworldliness of the Wolfen as a species.

Along with Wadleigh, the film also lost its original editor in the guise of Richard Chew, who had won an Oscar for his cutting on “Star Wars.” Four editors would replace Chew - Marshall M. Borden, Martin J. Bram, Dennis Dolan, and Chris Lebenzon – and perhaps this is an indication of Orion's insecurity on where to go with Wadleigh's picture. Safan's musical score was thrown out, with James Horner brought in to compose a new score. Horner was seen as another fresh new talent, but had not yet broken out with his music for the “Star Trek” franchise yet. “This was an interesting film,” he told Starlog in 1982, because another composer had scored the film. The music was disliked by the producers: the score was an abstract score, which would not work on the picture. It was a very noisy, avant-garde, atonal score. Everybody had nothing to relate to. It didn't have any emotional quality.” Horner scored just under an hour of the film in twelve days. Some of Safan's music remained, and it was supplemented by Horner's music for a previous Orion horror picture, “The Hand” (1981). Sadly, it is impossible to properly hear Safan's full score as integrated in the film. Nevertheless, Horner's score is impressive if traditional, and it would become a template for several of his scores, including the towering “Aliens” (1986).

“Wolfen” was released on July 24th, 1981 to a decent critical response but a poor box office showing. Roger Ebert was a fan of the picture, stating that it was an “uncommonly intelligent treatment of a theme that is usually just exploited,” and that Orion had dropped the ball with what little marketing they gave the film. Ebert was correct, it's a fine film and somewhat of the odd one out in a year of werewolf movies with intricate make-up showing human faces twisting into horrific creatures. “Wolfen” has no such easy answers, and that is one of its gifts. Its others include terrific performances by its cast, particularly Albert Finney and Gregory Hines, the wonderful cinematography, and the haunting “Alien Vision”, which should be better recognised for the trendsetter it was. But Michael Wadleigh isn't keen to present any kind of new cut of the film. “It was so long ago that I don’t think it can be done. I would welcome a re-release as it is right now, because I think, as I gather you do, that it’s a hell of a film, no matter whether it was recut or not. It’s got a lot of innovative stuff in it, and beautiful photography and thrills and chills, and I think that people might be amazed at the success it could have.”

The film ends with an epilogue of the Wolfen running away as Wilson commentates on their being. It's an appropriate ending and leaves us thinking about what “Wolfen” is about, and our own place in this world, and our own security. Or lack thereof.

“In arrogance, man knows nothing of what exists. There exists on earth such as we dare not imagine. Life as certain as our death. Life that will prey on us as we prey on this earth.”

Note: An earlier draft of this article appeared in Scream magazine.

Charlie - Excellent evaluation and some new perspectives on a film I've always enjoyed and wish had a better reputation! Well done!

I was a little boy growing up in the 70's and 80's and yes, I remember the GREAT 3 movies, two that were about traditional werewolf folklore and Wolfen that is something with a message. It was to high brow for its time but may not be amazingly today. I have it on dvd and I watch it often. And as much as enjoy the other two "traditional" werewolf movies, I prefer this one for its pseudo attachment of sorts to our living world. It is a SUPERB THRILLER. Spiritual actually. Even with the gore.